Early musings on the midterm results

The big picture is still complicated, but it’s clear this is not how Republicans hoped things would go

The 2022 midterm cycle has been unlike any other I can recall. Historically, the party of the president loses seats in Congress and state governments in midterms elections. However, in the months before Election Day, there were numerous conflicting signs about which party might have the advantage this time. The aforementioned trends plus high inflation worked in favor of Republicans. Conversely, several GOP candidates espoused extremist views that were off-putting for many voters, and the enthusiasm generated by the backlash to Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision (which overturned Roe v. Wade) appeared to have energized Democrats.

The polls also consistently showed that both parties were competitive this year. For instance, not since October 2021 had either party held more than a two-point lead on the generic ballot, which asks voters which party they want to control Congress. (Traditionally, one party has a clear advantage, especially as the election approaches.) And, ahead of Election Day, polls in more than half of the battleground Senate races showed the leading candidate with less than a four-point edge over their opponent.

In essence, the months leading up to Election Day offered a choose-your-own-narrative landscape in which people could cherry-pick data to make their theory of the case for each party. If you assumed history, Biden’s low approval ratings, and a troubled economy—or what we might call the “fundamentals”—would be the most important factors, and that the polls might be off again, you figured Republicans would have a good election night and possibly even enjoy a “wave.”1 If, however, you thought the polls showing a tight race were accurate, Republican candidates’ extremism would turn off moderate voters, and people would turn out in droves to save abortion rights, you could argue that Democrats might defy historical trends and not only not lose seats but possibly even gain some.

As the results began trickling in on election night, it quickly became apparent that the reality would fall somewhere in between, and possibly closer to the latter scenario. The party in power (the Democrats) was not going to face a wave that pushed scores of its members out of office. However, the “out” party (the Republicans) was still going to notch some notable victories. While the final picture is still coming into focus, it’s clear this midterm is a historical anomaly. We’ll be learning more in the weeks and months to come, but for now, here are some things we know.

1. Democrats had one of the most successful midterm elections for the party in power in modern history.

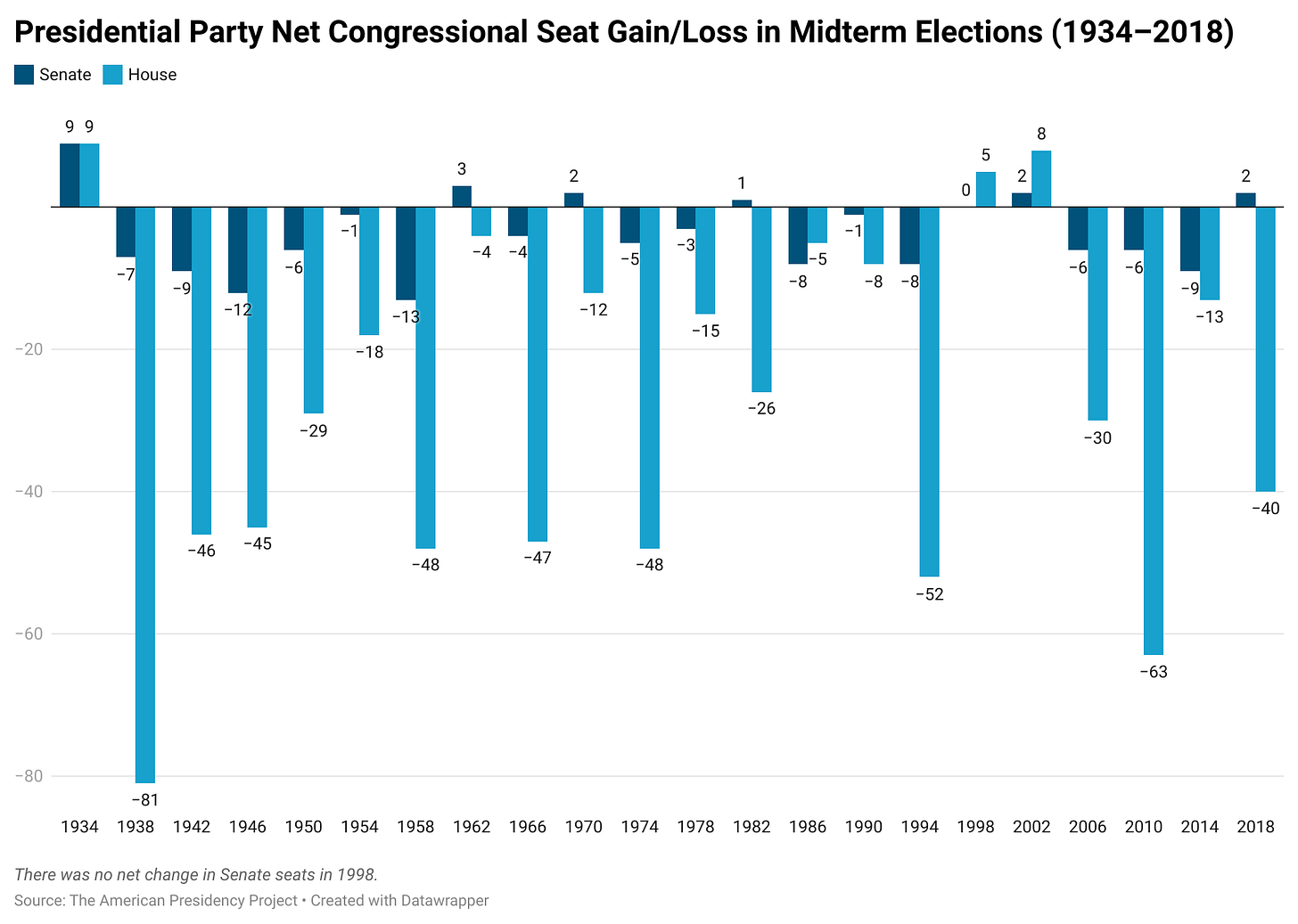

Relative to expectations, Democrats have pulled off something of a political miracle. Over the last 90 years, the president’s party has lost an average of 27 House seats and four Senate seats in midterm elections. For presidents whose approval rating is under 50% (as Biden’s has been since last summer), those numbers are 36 and five, respectively. And the losses often don’t stop there: the party in power often bleeds seats down the ballot as well, including governorships and state legislative chambers.

However, this has not happened for Democrats this cycle. On the contrary, with the caveat that there are still some key uncalled races, the party has, so far:

Successfully defended all of the Senate seats under its control and flipped one Republican seat

Successfully defended all but one governorship under its control and flipped two Republican seats

Defended the vast majority of its House seats that were rated “toss-ups”

Flipped at least four state legislative chambers (and likely lost none)

Defended several other key downballot offices in competitive states

As of Saturday, Democrats looked poised to either hold steady or gain one Senate seat and compete to retain their control of the House. To put the party’s performance in these races into historical perspective: this is only the third time in the last 90 years that the president’s party did not lose any Senate seats and lost fewer than 10 House seats in his first midterm election.

2. There were bright spots for Republicans as well.

Although they underperformed in a big way relative to expectations, it wasn’t all doom and gloom for the GOP. As things stand, the party looks on track to win the national House popular vote by about four points—a sign of an overall Republican-friendly environment. Unfortunately for them, this did not trickle down uniformly across the country, which explains why Democrats succeeded in defending so many of their seats. So, the GOP’s modest advantage in the national House vote may ultimately be more of a consolation prize. But even despite that, they are likely to wrest control of the House from Democrats, albeit with a very narrow majority. Part of the reason they are on track to do so is because of the success they saw in, of all places, deep-blue New York, where they have flipped at least four congressional seats. Republicans also won a hotly contested race for governor in the swing state of Nevada, which broke up Democrats’ governing trifecta there. And then, there was Florida…

3. Florida may no longer be a swing state.

It was just 10 years ago that Barack Obama carried Florida’s electoral votes for a second straight election. In the next several general elections, Republicans eked out wins by the slimmest of margins in races for governor, Senate, and the presidency—always putting it just out of reach for Democrats but close enough to keep them coming back. However, after the state appeared to slightly shift away from the party in 2020, a red wave did materialize there this year, as Democrats were annihilated up and down the ballot. Governor Ron DeSantis and U.S. Senator Marco Rubio, both Republicans, each won re-election by more than 15 points. Notably, DeSantis became the first GOP gubernatorial candidate to carry Miami-Dade County—a heavily Hispanic, traditionally Democratic stronghold—in 20 years.

Republicans also flipped a handful of House seats in the state that were gerrymandered to disadvantage Democrats. Additionally, they won a supermajority in the state legislature. And, if that weren’t enough: Democrats were locked out of all statewide offices for the first time since the Reconstruction era. I plan to explore the reasons for this shift in the Sunshine State in a future post, but suffice it to say it is unlikely to be on Democrats’ radar for the foreseeable future.

4. Several “election deniers” won, but not many did in places that aren’t deeply Republican.

Republican candidates who peddled in conspiracy theories about the results of the 2020 election—including some who were at the Capitol on January 6—generally did not fare well in competitive races. There were six candidates running who disputed the 2020 election results and whom Democrats worked to prop up in primary elections this year over more mainstream alternatives, and all six lost. Additionally, these types of candidates ran in 31 races considered to be “toss-ups” or “leaning” toward one of the two parties, and as of Saturday, just nine had won. In seven remaining competitive contests that had not yet been called, election deniers led in three (though Democrats have a path to winning in all of them).

However, while six of the seven Republicans running for Congress who were at the Capitol insurrection lost their races, one of them won (and will thus be returning to the Capitol). More troubling still: fully 155 candidates who peddled in 2020 election conspiracies won their races as well, and one (Joe Lombardo in Nevada) might be in a position to make the certification of the 2024 presidential results difficult. But outside of Lombardo (and possibly Kari Lake in Arizona), these types of candidates were shut out of major offices in swing states, including all election deniers in those states who ran for the top office that oversees elections. This means that in the next presidential election, the officials responsible for counting and certifying votes are unlikely to cause any unnecessary problems in the process.

5. High inflation and cost-of-living issues weren’t fatal for Democrats.

Historically, when voters are hurting economically, the president’s approval rating tends to go down—and, with it, his party’s midterm fortunes. This was the recipe in place heading into the midterms, with inflation at 7.7%, President Biden’s approval rating mired in the low 40s, and polls making it very clear that economic issues were at the top of voters’ minds. Most analysts expected that high inflation would be an albatross around Democrats’ neck this year, as they were the party in power.

Ultimately, however, the economy was not as effective a cudgel as Republicans, who didn’t offer voters many solutions of their own, had hoped for. Though they disproportionately won the 48% of voters who identified the economy as the top issue facing the country, the party’s advantage with them was nearly half (34 points) Trump’s margin with those same voters in 2020 (64 points). Additionally, and possibly most tellingly/importantly: while voters who thought the economy was “excellent” or “good” overwhelmingly backed Democrats and those who thought it was “poor” broke heavily for Republicans, people who only said it was “not so good” (44%, a plurality of all voters) supported Democrats by nine points. So, despite all the pre-election handwringing over how the economy might drag down Democrats, it does not seem that voters laid the blame for these problems solely at the feet of Biden and Congress.

6. It’s unclear how much the abortion issue helped Democrats.

Many observers also wondered about the extent to which the threat to abortion rights would serve as a bulwark for Democrats against expected midterm losses, and I would posit that the answer to this is a little murky. I think it most likely helped awaken the Democratic base, and a point in favor of those who think the Dobbs ruling was a “game-changer” is that pre-election polling showed that the court case made half of all voters (including 69% of Democrats) more motivated to cast a ballot. Moreover, according to the AP VoteCast exit poll, voters who identified abortion as the nation’s top issue broke heavily for Democrats, 77–20%. However, it doesn’t appear to have been the top issue for nearly enough people to have been decisive in this election: just 9% of voters overall said that it was the most important issue facing the country.2

Some have also pointed to the results in five states that voted on abortion ballot measures: in all of them, voters came down on the side of protecting abortion rights. However, across those states, Democratic candidates underperformed the “pro-choice/defend abortion rights” option by an average of 11.4 points, meaning some voters showed up to protect abortion rights but did not vote for the Democrats. In Michigan, for example, a referendum enshrining abortion rights into the state constitution outran Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer in 76 of the state’s 83 counties, and eight counties voted for the measure while backing Whitmer’s Republican opponent.

Moreover, there’s no sign that states with these ballot measures generated higher turnout relative to the 2018 midterms than others did. Turnout was up in Michigan (which had a competitive race for governor) and Vermont but down in California, Kentucky, and Montana.3 I take all this to mean that while the Dobbs decision raised the stakes of the midterms and likely convinced some jaded Democrats to get out and vote, it is still difficult to prove that it was the primary factor in the the party’s stronger-than-expected performance.

7. Democrats’ success hinged on reaching outside their base.

Perhaps the biggest reason for the lack of a GOP wave is that Democrats successfully convinced voters who were not already part of their base to back their candidates. This includes, foremost, independent voters. For the first time in recent memory, not only did independents not break overwhelmingly against the party in power; they broke every so slightly in favor of them. Democrats nationally appeared to carry these voters by 2–3 points.

Similarly, “meh” voters—a term coined by the Cook Political Report’s Amy Walter to describe voters who “somewhat disapprove” of Biden’s job performance—broke evenly between the parties, 47–47%. This stands in contrast to 2018, a blue wave midterm year in which voters who “somewhat disapproved” of then-President Trump heavily backed Democrats. The party’s gains with these two groups were vital to its performance because early data indicates that Republicans made up a disproportionate share of the electorate this year. So, if these groups had performed as they historically have—breaking for the “out” party—it could have been a bloodbath for Democrats.

8. Despite our hyperpolarization, some voters are still splitting their tickets.

Related to the previous point: perhaps an encouraging sign that persuasion efforts still work with at least some American voters is the fact that there were numerous instances of ticket-splitting this cycle. In at least five states—Kansas, Nevada, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Wisconsin—voters backed one party in their Senate race and the other in the governor race. (Arizona and Georgia, which still have uncalled races, could increase that number to seven.) Notably, in Kansas, New Hampshire, and Vermont, the partisan splits were massive: 25.4 points, 24.7, and 87.6 (you read that right), respectively.4

Even in states where one of the parties won both races, there were still meaningful levels of ticket-splitting. For example, in Ohio, Republicans won both contests, but Democrats’ Senate candidate outperformed their governor candidate by nearly 10 points, which may have helped the party flip two House races down the ballot. In Georgia, Republican Governor Brian Kemp won re-election by 7.6 points while Republican Senate candidate Herschel Walker was forced to a runoff election against incumbent Democratic Senator Raphael Warnock.

That said, there is evidence that, since the late 1980s, Americans have become less willing to vote for members of both parties in the same election—a sign of our growing political polarization. But even if these results don’t portend a new dawn of bipartisanship in the years ahead, they can give us some faith that many of our fellow Americans still have complex, nuanced views and are open to changing their minds.

9. Democrats still appear to have a Hispanic problem.

One of the biggest storylines from the 2020 election was the erosion of Democratic support among Hispanic Americans. Long thought to be a core part of the party’s coalition, the results from that election indicated they were becoming more of a swing group with heterodox interests and views that were not uniformly aligned with either party. Heading into the midterms, polling showed that Democrats were still struggling to bounce back with these voters.

While we won’t have a great picture of the overall story until later, early signs do not bode well for the party’s hopes of accomplishing this. According to the AP VoteCast exits, Republicans nationally won a full 40% of Hispanics, a greater share than in any cycle since 2004, when George W. Bush won 44%. Democrats did still appear to win Hispanic voters by 16 points this year. But while that may sound like a decent margin, it is down from their 25-point edge in 2020 and from 35 points in 2018.

We also have more concrete evidence from two states with large Hispanic populations that have reported most of their votes: New Mexico and Texas. On average, counties in both states where the citizen voting-age population is either plurality- or majority Hispanic shifted toward Republicans from 2020 about as much as each state as a whole did. This means that those heavily Hispanic counties did not perform better for Democrats than the statewide average in either state.

In California, which is still counting votes, it looks like Hispanic voters may have actually shifted even further rightward compared to 2020. It’s clear the party still has some structural issues to figure out with this fast-growing voting bloc moving forward.

10. The polls were largely accurate this year.

This cycle was a big one for the polling industry. After huge misses in 2016 and 2020, when most polls failed to properly capture support levels for Trump, many saw the midterms as a test of whether pollsters had fixed their problems or the industry was irreparably damaged. Polling is a vital tool in any democracy. It gives the public a say on matters impacting the country during times of the year when there are no elections, and it also provides lawmakers with feedback to understand what their constituents want. So thankfully—both for the pollsters’ jobs and for our democracy—the polls were pretty accurate this time around. Of the 11 Senate races that were considered at least somewhat competitive this cycle and included a Democrat and Republican, just three had polling misses of more than four points.

11. Losing candidates are actually conceding.

In the months leading up to the election, fears grew that so-called “election denier” candidates would force our election system to undergo a stress test if they lost and would not concede to their opponents. For the most part, however, this amounted to nothing at all (with a couple of high-profile exceptions). In a sign that they likely did not believe their own sophistry, most Republicans who ran on the fiction that the 2020 election was stolen have conceded when they lost their races.

This may be little comfort for many, especially following months of hints from these very candidates that they might cause trouble if the results were close. But for now, one more democratic norm lives to fight another day.

12. Be prepared for close elections for much of the foreseeable future.

Unlike in decades past, when the country would line up behind one party or the other seemingly in unison because a candidate or party’s ideals offered such broad appeal, elections today are increasingly decided by just a handful of voters in a handful of states. While I lauded above the fact that some voters do still split their tickets and that independents’ performance showed that true “swing” voters still exist, most of the country is deeply divided.

This means that each party can bank more votes on their side than ever before and only needs to win a small slice of the country to produce major swings in one direction or the other. Consider: Trump became president in 2016 because of 77,000 voters in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. He then lost in 2020 thanks to just 42,000 voters in Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin. Each of those results had massive repercussions for the country. So long as Americans remain highly polarized, expect more elections decided by razor-thin margins that have huge consequences.

To be fully transparent, I leaned more toward this camp.

If you read this and thought, “Wait, I saw something saying that 27% of Americans picked abortion as their top issue,” it’s because you likely saw the Edison Research exit poll. Please read this thread to learn why I highly distrust that poll and that 27% figure.

This is according to preliminary estimates, which could change in the weeks ahead.

Hey, Michael, I've heard some people saying that polling before election day is not as accurate anymore because it relies on phone calls...which us millenials and gen z avoid like the plague. Is that true or are other polling methods being used now?