Can Democrats defy midterm gravity?

Making sense of recent shifts in the national political terrain

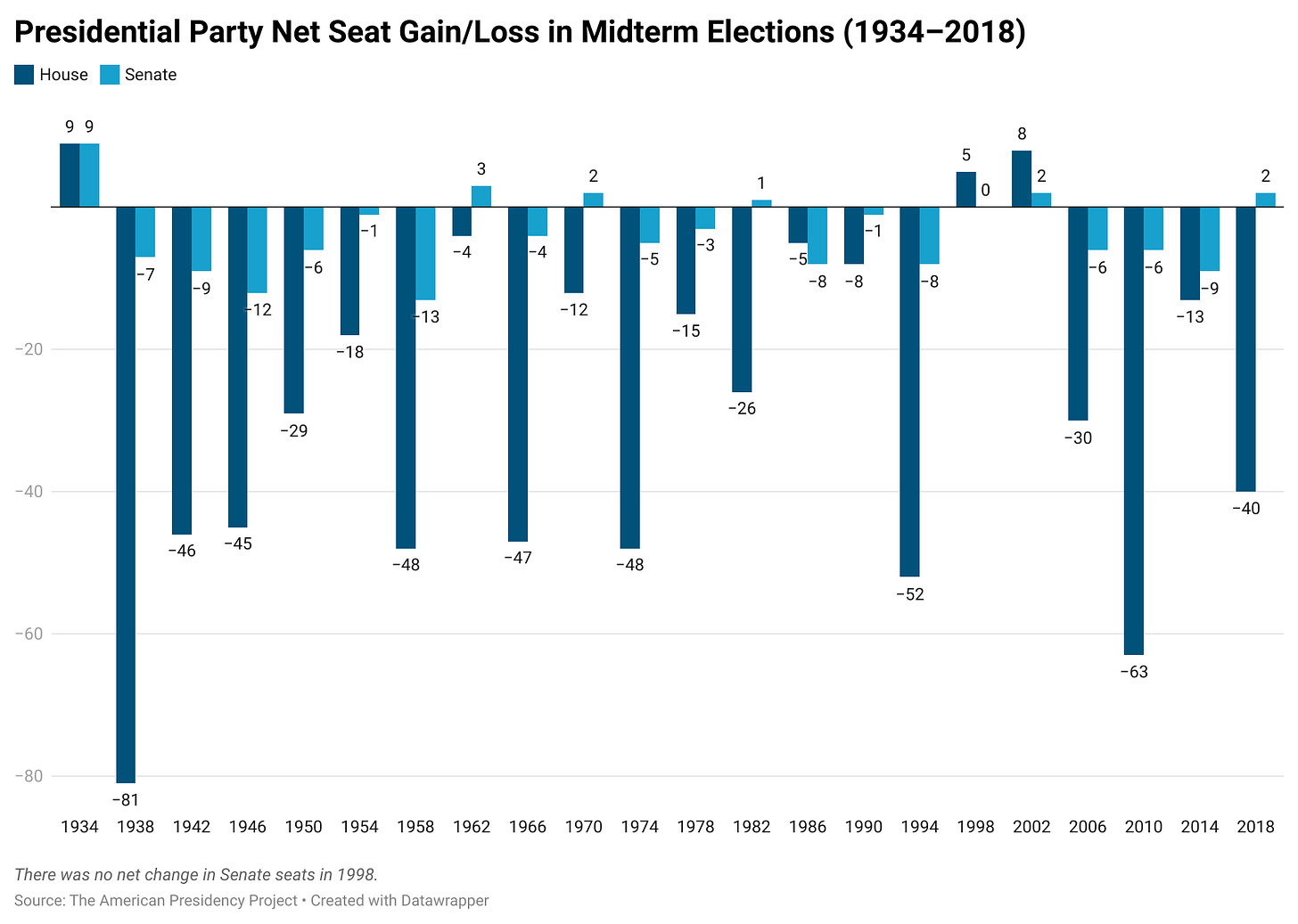

It has been a political truism for decades: the president’s party tends to lose seats in Congress and down the ballot in midterm elections. Going back nearly 90 years, the party controlling the White House has averaged losses of 27 House seats and 4 Senate seats in these cycles.

Moreover, the extent of those losses are often worse for presidents whose approval rating is underwater. Since 1946, when a president has entered a midterm with an approval of less than 50%, his party has lost an average of 36 House seats and five Senate seats.1

There are numerous possible reasons for this trend, including that the “out” party (i.e., the party that doesn’t hold the presidency) is often more enthusiastic about voting to win back power in the legislature and slow the president’s agenda, and that voters usually view the president as the person to be blamed when things aren’t going well in the country, as the buck theoretically stops with him.

With this context in mind, many political prognosticators and analysts believed throughout late 2021 and into 2022 that a “red wave” midterm election, which would sweep Republicans into power in both Congress and the states, was either likely or inevitable. And there was reason to think they were right: in addition to the traditional midterm penalty the president’s party often faces, there was a deluge of deflating news for President Biden starting last summer, including the botched troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, a post-vaccine resurgence in COVID, and growing economic problems (specifically, rising inflation). All this corresponded with a gradual, unrelenting decline in his approval rating. Moreover, in the first meaningful elections under his presidency, Republicans made major inroads in blue-trending Virginia and even reliably blue New Jersey in fall 2021.

However, one year can be a lifetime in politics.2 Though the sour economic news and Biden’s paltry approval lingered into 2022, several major events this summer seem to have turned the conventional wisdom of an impending Republican midterm romp on its head. Perhaps the most important one was the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in the case Dobbs v. Jackson, opening the door to total abortion bans in a number of states (and possibly even nationally).

Key indicators support the idea that the Dobbs decision was a gamechanger. One of the best ways to take the pulse of the electorate and gauge how it might vote in November is by looking at the results of special elections that take place in the months before.3 As FiveThirtyEight helpfully outlined, in the special House elections held before Dobbs, the results were about two points more Republican than those districts’ baselines. However, in the four special elections that have taken place since Dobbs, Democrats have outperformed their baseline in all of them—and by an average of nine points. Just this week, Democrat Pat Ryan won one such contest in New York’s 19th District, which Biden narrowly carried in 2020 by 1.5 points, making it a good national bellwether for gauging the electorate’s mood. Normally, a district like this would be a prime pick-up opportunity for the “out” party. But, despite the GOP fielding a high-quality candidate, Democrats turned out at a disproportionately higher rate than Republicans, helping Ryan not only win but outperform Biden by 0.7 points.

In addition to these results, polling has improved across the board for Democrats in recent weeks. In the generic ballot, which asks voters which party they want to control Congress, Democrats went from trailing Republicans by a little more than two points in late June—around the time of the Dobbs decision—to now leading them. Plus, following his string of legislative wins (and a slightly improved economic outlook), Biden’s approval rating has also ticked up four points over the past month. And in races for Congress and governor, Democratic candidates are running ahead of their Republican opponents across the board.

However, despite these growing signs of optimism for the party, it is worth exercising caution in interpreting these shifts. As we have established, a lot can happen in a very short time in American politics, and given that we are still closer to the day the Supreme Court delivered its Dobbs decision than we are Election Day, there is plenty of time for the landscape to change again. As folks debate whether Democrats can overcome history and prevent substantial losses this fall, there are several factors to consider:

Special elections are not general elections. This may sound obvious, but while special elections can tell the story of the national mood and indicate which party has more momentum, they also tend to be lower-turnout affairs that attract high-information voters. As the Democratic coalition has shifted in recent years, it increasingly comprises more voters who are college-educated and likelier to be plugged into current events. Indeed, such voters have fueled Democrats’ overperformances in these post-Dobbs contests. However, in an election that attracts more national attention (such as the November midterms), it’s probable that other voters who are not as friendly to Democrats will turn out in higher numbers than they have thus far.

Higher turnout doesn’t necessarily equal Democratic success. In the 2018 midterms, Democrats experienced a wave election of their own, netting 40 House seats and making significant gains in the states. That cycle was notable because turnout reached historic highs, driven primarily by Democratic voters. By contrast, the 2014 midterms saw historically low levels of turnout, which corresponded with massive Republican gains. These results led some Democrats (and even Republicans) to believe that the greater the number of people who voted, the better the results were for Democrats, because voters who tended to sit out elections were likelier to lean left.

However, the 2020 presidential election alone put that notion to rest, as it saw the highest turnout in over 100 years, and, though Biden did ultimately oust Trump—a rare feat in a presidential race—Republicans saw far more success down the ballot than did Democrats. Then, in the Virginia governor race last fall, high turnout led to a Republican sweep in the state. More broadly, several studies have found that neither party really has an edge when turnout is higher. So, even though Democratic enthusiasm in the post-Dobbs world has produced higher turnout in special elections and even some party primaries and could keep Democrats competitive this November, it’s not clear that it will be enough to stave off Republican gains.

Democrats likely need a wider generic ballot advantage. As election analyst Elliott Morris notes, institutional biases against the Democrats mean they probably need to build their advantage in the generic ballot to at least four points over Republicans to, at minimum, not lose seats:

Polling non-response bias may be skewing things. One rationale for why the polls in 2016 and 2020, which wrongly portended massive Clinton and Biden wins in several swing states, might have been off is because of a partisan difference in who answers the phone when a pollster calls. There are several reasons for this phenomenon, called non-response bias. In an era of caller-ID, many people simply don’t answer the phone if they don’t recognize the number calling. Additionally, some research has found that people who feel more isolated or alone are less likely to respond to polls, and these voters have been more inclined to vote for Trump. Others have posited that voters who supported Trump began to distrust pollsters and either not answer their calls or not truthfully tell them their vote intention. Whatever the cause, this reality can lead to polls producing skewed results.

Some have pointed out that other recent polling—in the 2018 midterms, the 2020 Georgia runoffs, and the 2021 Virginia governor race—has been more accurate and should be a sign that the problem with non-response bias was exclusive to elections when Trump was on the ballot. This is possible, but we don’t know that for sure, and at any rate, Trump figures to be a factor to some degree in this year’s elections. Moreover, the New Jersey governor election that occurred the same day as Virginia’s last year produced a result that was much less accurate.4 So, while the polls might help capture, say, a surge in Democratic enthusiasm following Dobbs, it’s worth expressing a healthy dose of skepticism that this movement is a harbinger of Democratic success in November, especially when you see polling showing the party’s candidates running ahead of their opponents by double digits in a competitive swing state.5

Biden’s approval is still in dangerous territory. Although Biden’s approval rating has gotten a boost over the past month, it is still low enough that it could be a drag on his party. According to FiveThirtyEight’s polling tracker, roughly 41.5% of Americans approved of his job performance as of this week compared to 53.8% who disapproved. While that is certainly an improvement over much of the summer, it is still the second-lowest pre-midterm approval of any president in the modern era (behind Bush in 2006) and the lowest for a president heading into their first midterm. It’s possible that Democrats will be able to overcome this. Indeed, polling has shown the party’s candidates running in Senate and governor races routinely performing much better than him among voters in their states. Still, if history is any guide, his low approval is likelier to hurt his party than to be a non-factor.

The economy reigns supreme. While abortion has clearly become a more potent voting issue since the Dobbs decision, voters on the whole still seem to worry about the economy more than anything else. Poll after poll shows that inflation remains the most important issue in swing states. Moreover, as the Cook Political Report’s Amy Walter has noted, voters remain sour not just about the state of the economy but about its prospects for improving anytime soon—attitudes that can take a long time to rebound. This reality might give Democrats a rude awakening: in the two major elections we have held since the pandemic-induced economic turmoil began, a plurality of voters ranked the economy as their most important issue—and they overwhelmingly backed the Republican candidates in those races.

Democrats appear intent on trying to turn around their midterm fortunes using abortion as a path forward. However, the results of the abortion referendum in Kansas earlier this month showed that not only has their base already been activated by this issue, but it’s unclear whether it will be enough to win over voters who aren’t already in their camp. If they aren’t also pushing a message about the economy, they risk losing working-class voters for whom the issue is top of mind and whose support they will need to get across the finish line in key races.

None of this is to say the recent signs of Democratic momentum aren’t real. On the contrary: it’s hard to see how the party hasn’t begun to upend the year-long narrative that they are barreling inexorably toward a midterm wipeout. Still, there are over two months until Election Day, and a lot can change during that time. While it may seem that Democrats have the wind at their backs right now, it needs to be strong and durable enough to overcome major obstacles that traditionally hold the president’s party down in midterm cycles. Time will tell whether they’re capable of doing that.

Conversely, the president’s party rarely sees a net gain in seats. This has happened just 6 times in the Senate and only three times in the House over the past century, often due to major national events: the Great Depression and FDR’s New Deal, the Republican impeachment of Bill Clinton, and the World Trade Center attacks on 9/11.

Increasingly, these days, one week can feel the same way.

These are typically elections for vacant offices that need to be filled.

In fact, one New Jersey pollster’s final survey was off by so much from the final results—it showed the incumbent governor, who won re-election by just 2.8 points, winning by 11—that he issued a public mea culpa and pondered whether it was time to get rid of election polls altogether.

And especially after we saw the exact same thing happen in 2020.