How Kansans saved their abortion rights

And what it can tell us about how this issue might impact the midterms

After the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade earlier this summer in its landmark Dobbs v. Jackson decision, the country faced unfamiliar terrain: for the first time in decades, the right to an abortion was no longer something all Americans enjoyed. The procedure was immediately outlawed in a handful of states, and some Republican-controlled legislatures began working to make it illegal in their states as well.

These legislative efforts were a reminder that while abortion has long been one of the country’s most fraught cultural issues, it is also necessarily a political one. Although polling has long shown that the public generally favors some restrictions on abortion, it is overwhelmingly against banning it outright. As these new state restrictions have begun setting in—many without exceptions for rape, incest, or the health of the mother—some Democratic Party strategists have suggested that the threat of total bans might help mobilize their voters ahead of this year’s midterm elections.1 Indeed, Republicans’ advantage on the generic ballot, which asks voters which party they want to control Congress, has evaporated since the Roe was overturned, and there is evidence that abortion has grown as a top voting issue over the past month.

That said, polls are not votes, and they can only tell us so much about the myriad factors that might influence an individual’s decision at the ballot box. So it’s worth asking: in the face of numerous problems facing the country (inflation, high gas prices, etc.), will threats to abortion access actually become a top voting issue in a post-Roe world? And, if so, might it shift the midterm equation more in Democrats’ favor?

Coincidentally, more than a year before the Court’s decision, Republican legislators in Kansas voted to send a measure to the 2022 primary ballot asking voters to amend the state constitution to clarify that it does not protect Kansans’ right to an abortion. This meant that voters would have a say on this issue just weeks after the Court struck down Roe, giving the country its first glimpse at how this new landscape might look. Here’s how the vote on the amendment, called “Value Them Both,” would work:

A “yes” vote would say the state constitution does not guarantee the right to an abortion, opening the door for the legislature to pass a full ban

A “no” vote would reaffirm that the right to an abortion exists in the state constitution

Pre-election polling showed that the vote was expected to be close but that the “yes” side held a slight advantage. However, those polls did not appear to capture the high levels of enthusiasm that voters had on this issue—and how that would shape the outcome of the vote. On Election Day, Kansans, who backed Donald Trump for president by nearly 15 points in 2020, surprised many observers by decisively rejecting the amendment, 58.8–41.2%.

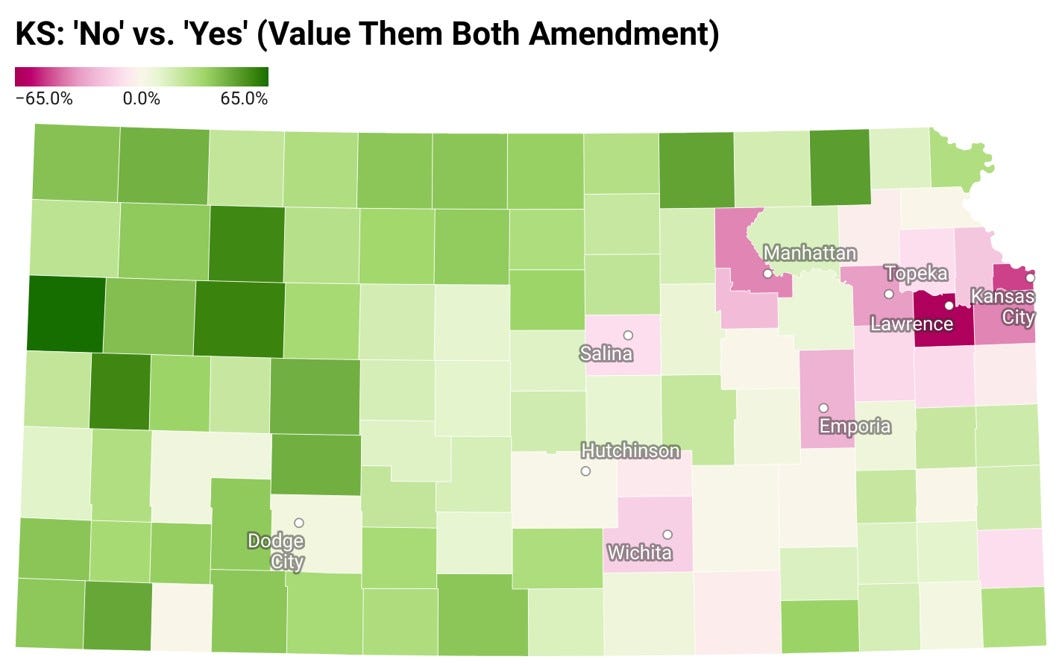

Perhaps even more surprising: it wasn’t just the state’s more liberal and populous counties that drove the measure’s defeat (though they played a key role). In several deeply red, rural counties, a majority of voters backed the “no” option.2 Using the state’s competitive 2018 governor race as a benchmark, we also see that even in rural counties where a majority voted “yes,” voters backed “no” (or what I’m calling the “liberal” ballot option) at a far higher rate than they did Democratic gubernatorial nominee Laura Kelly (the “liberal” option in 2018), indicating that most of the state swung left compared to four years ago. In fact, a whopping 93 of the state’s 106 counties moved leftward, and nearly half (47) did so by double-digit margins.3

Additionally, the aforementioned enthusiasm around this vote generated unexpectedly high levels of voter turnout. There were more ballots cast in this primary election than in each of the 2010 and 2014 midterm general elections. Fourteen counties, including populous Douglas (home to Lawrence and the University of Kansas), Shawnee (Topeka), and Leavenworth (exurban Kansas City), even saw turnout hit 90% of all ballots cast in the general election in 2018, when the country experienced record-high turnout. In all-important Johnson County—the largest in the state and home to the Kansas City suburbs—turnout was at 89.6% of the 2018 general election, with 242,827 people casting ballots compared to 271,017 four years ago.4

Combined with leftward swings across the state, the statewide “no” total (534,137 votes) was ultimately higher than Kelly’s total (506,509) in her 2018 victory and at 93.7% of Joe Biden’s total (570,323) from the 2020 election. In other words: based on what we know right now, it looks like abortion rights in Kansas were saved through a combination of energized liberal voters, who were fired up after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling, and persuadable moderates and conservatives who thought opening the door to a potential total abortion ban went too far.

So, how much can these results tell us about the fortunes of Democrats—the party known for championing abortion rights—in this November’s midterms? Of note, several other states will be voting on this issue in the general election, including ones with other competitive races on the ballot like Michigan and Colorado. Some analysts believe that abortion could convince suburban voters, a key group that swung leftward during the Trump years, to stick with Democrats in this year’s midterms, which would give the party a major boost.

However, as others have observed, Kansans essentially voted on this measure in a vacuum. There weren’t really other competitive elections on the ballot—at least not ones between Democrats and Republicans. So, while some independents and Republicans might have joined energized Democrats in voting down abortion restrictions, we don’t really know how the two former groups would have voted for party candidates in other races had they been on the ballot as well.

One post-election analysis found that roughly 180,000 voters only voted on the abortion measure but not the other primary races on the ballot. As Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball summarizes:

Put another way, about half of the voters who cast a ballot on the abortion issue voted in the Republican gubernatorial primary, while the other half was made up of people who either voted in the Democratic primary or just voted for the ballot issue. But the pro-abortion rights side got close to 60% of the vote. So, even if every Democratic primary voter and every ballot issue-only voter voted on the pro-abortion rights side (and surely a lot did, but not every single one), there still were some Republican primary voters who voted no.

With that, it’s going to be a question of how much those pro-abortion rights Republicans prioritize abortion. Even if they disagree with Republican candidates on the issue, is it going to override their concerns about inflation or the economy? Ballot issues sometimes create coalitions that do not carry over to partisan elections.

We also have evidence from recent elections to show that voters are willing to back the policy preferences of one party while voting for politicians of the other. In 2020, Florida voters overwhelmingly backed a ballot measure raising the minimum wage while they simultaneously voted for Donald Trump (who generally opposes that policy). In 2018, the state voted by nearly a 2–1 margin for an amendment restoring voting rights to ex-felons while it also backed Republican Ron DeSantis for governor (who later signed a bill undercutting the amendment). In 2016, 55% of Coloradans backed a measure increasing the minimum wage versus 48% who voted for Hillary Clinton (who favored doing that).

Essentially, in each of these elections, many voters backed the more liberal position on the ballot initiative but did not also vote for Democratic candidates who supported those positions. Moreover, polls continue to show that although abortion has gained traction as a top voting issue, the economy and inflation reign supreme—especially among the voters whom Democrats will need to win over to be competitive.

However, there is still good news for the party and abortion-rights advocates coming out of this election. For starters, Kansas is one of 13 states that Trump won where at least a plurality, if not a majority, of voters agree that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. At minimum, these results showed that even in deep-red states, abortion bans are not popular policy.

Additionally, it does look like this issue can indeed mobilize the Democrats’ base voters, including potentially some who may not have previously been enthusiastic about this year’s midterm elections. Beyond ballot measures, there will be races for governor, attorney general, and the state legislature in many states this November, all of which could have an impact on those states’ abortion laws in the coming years. Although Democrats have fretted about facing the traditional midterm penalty for being the party in power, an issue like abortion could rally their voters to at least keep them competitive with Republicans.

Ultimately, it’s difficult to extrapolate too much from Kansas’s results. There are simply too many unknowns about how this issue will influence voters’ decisions three months from now when they’re voting for numerous other races—all of which will be for offices that deal with more issues than just abortion. Still, Kansans made a statement this week: voters are wary of losing rights they’ve long taken for granted. In light of these results, it might be prudent for anti-abortion activists and the Republican Party to think twice about powering forward with a position that most voters—even many in deeply conservative territory—find too extreme.

The president’s party traditionally sees significant downballot losses in midterm elections.

In total, 15 counties that voted for Trump in 2020 voted no on the amendment.

Compared to the 2020 presidential election, every county in the state moved leftward by double digits.

For reference, statewide turnout for the 2022 primary was 86.5% of its 2018 total.