Partisan acrimony in Congress is at an all-time high. Where does it stop?

The January 6 insurrection was an inflection point for congressional relations

If you’ve followed any news about Congress this year, you’ve probably heard about one of the numerous tussles between higher-profile members of opposing parties. Cori Bush vs. Marjorie Taylor Greene. Paul Gosar vs. AOC. Lauren Boebert vs. Ilhan Omar. While congressional relations have been souring for the better part of the past three decades, they’ve grown noticeably worse since the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol last January 6. Disputes now aren’t just a matter of normal partisan differences; they are increasingly and often based on personal animosities.

As we approach the one-year anniversary of one of the darkest days in American history, it’s worth asking: just how bad are today’s divisions in Congress compared to other points in our history? And, with things at such a low point, how does this period end?

It’s first important to grapple with how we got here. Political observers often trace this era of partisan combativeness to the 1994 midterm elections, when Republican Newt Gingrich launched a hardball campaign aimed at helping his party win back the House of Representatives. Gingrich’s pugilistic style has been credited with ushering in a new era of partisan rancor and making politics bloodsport.1 Core to his philosophy was the idea that working in a congenial manner with one’s colleagues of the opposing party to govern was a sign to voters that government was functioning generally well and that there was no need to “throw the bums out.” This previous mode of operating had left one party — Gingrich’s Republicans — more or less locked into minority status for four straight decades.

During the midterm campaign, Gingrich also promoted the idea that members who relocated their families to Washington after they were elected eventually succumbed to “Potomac fever” and began losing touch with their constituents. One of the most underrated and impactful changes from this period was when members started to see it as politically disadvantageous to live in DC full-time. Many began choosing to keep their families back in their districts and only traveled to the capital a few days a week for essential work. Political scientists often identify this shift as a key contributor to the breakdown in congressional relations. Rather than immersing themselves in their new city of employment and finding opportunities to forge relationships with colleagues, members of Congress became estranged from one another. Increasingly, many of their interactions with members of the other party came either in highly partisan committee hearings or hyper-segregated floor activity.

This declining familiarity and trust between members of opposing parties, combined with Gingrich’s zero-sum views on how to obtain power, left both parties less reluctant to attack their colleagues and the minority party more emboldened to obstruct the majority’s agenda at every turn. In the years following the Gingrich revolution, this has materialized in near-uniform obstruction—especially from Republicans—on most legislation, including an unprecedented rise in the use of the filibuster in the Senate to block major-party legislation:

However, the breakdown in bipartisan legislating is not solely due to these changes around norms. This period also coincided with members’ own ideologies growing further and further apart. According to the project VoteView, the gap between the median Republican and median Democrat in Congress, which has steadily increased since the 1990s, is not just the widest today it has been since the years immediately preceding the Civil War — it’s even wider.

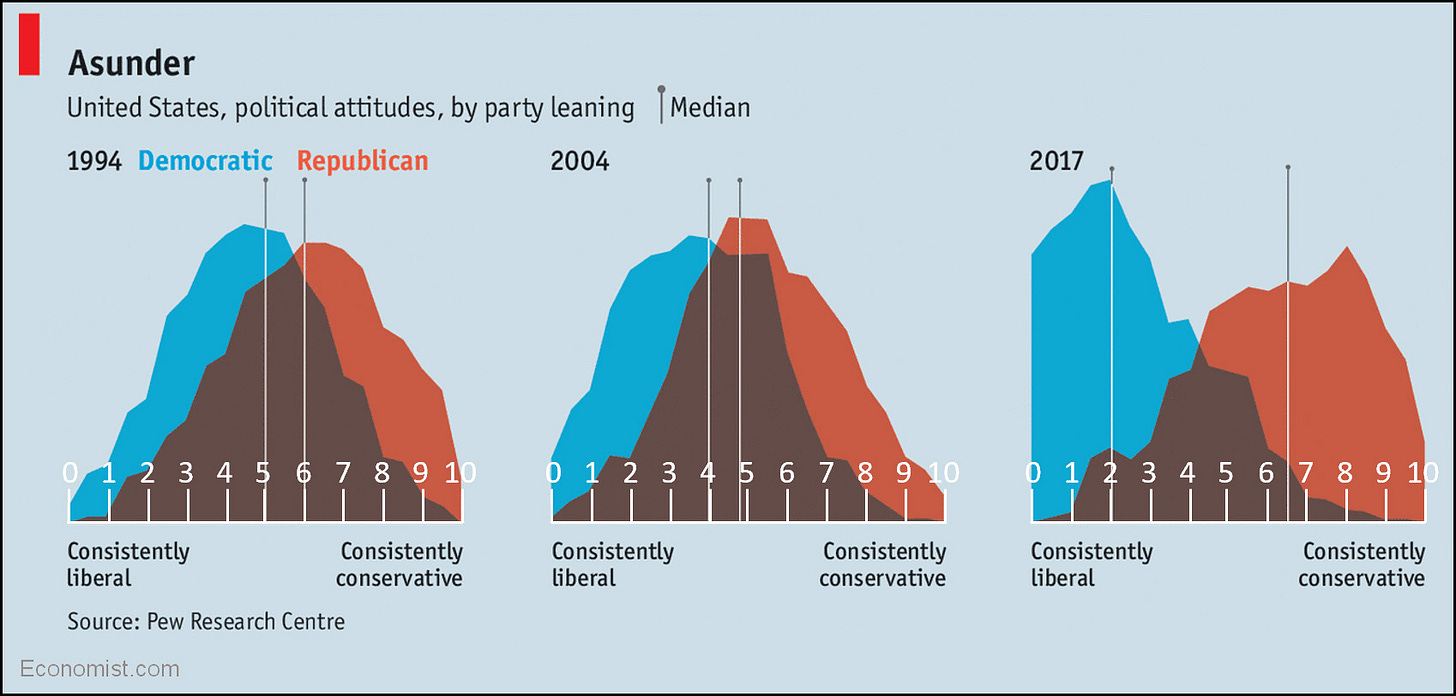

Congress’s divisions have mirrored — and possibly even been a product of — increased polarization in the American public. For instance, President Joe Biden’s 87-point gap in partisan support is the highest for any president going back to at least the 1950s, with the second-largest gap (76 points) belonging to his predecessor, Donald Trump. Moreover, the ideological gap between self-identified Democrats and Republicans has exploded over the past decade or so, while levels of distrust of people on the “other side” have grown to alarming levels.

Making matters worse, the rise of social media in the late 2000s began moving public dialogue from the physical realm to a more digital one, making it easier to dehumanize one’s online interlocutor. And geographic sorting—the increased segregation of partisans along urban/rural lines—has led to a nation that is less familiar with its neighbors and a politics (and Congress) that reflect that.

All of this came to a head with Donald Trump and the 2020 presidential election. Trump was a uniquely divisive character in recent U.S. history whose presidency worsened the tensions already at play in the country. After losing re-election to Joe Biden, Trump and other Republicans spent weeks spreading baseless conspiracies claiming the election had been stolen from him. And, on January 6, 2021, Trump whipped some of his supporters into a frenzy at a Washington, DC, rally, after which many in attendance joined in violently attacking the U.S. Capitol building to stop the certification of Biden’s Electoral College victory. Among the memorable moments from that awful day was when, as the Capitol was being breached, Democratic Rep. Dean Phillips shouted at his Republican colleagues, “This is because of you!” As rioters made their way through the Capitol, many members feared for their lives. And yet, after all that, 140 Republicans in the House and seven in the Senate proceeded to vote against certifying the election results anyway.

Since that grim day, the contentiousness and divisions that have increasingly pervaded Congress over the previous three decades have gone from being mostly ideological to more personal in nature. Relations between the two major parties’ leaders are virtually nonexistent. Members of opposing parties by and large do not trust each other—especially in the House. Democratic Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, who has served in Congress since 1981, has said of the current environment, “It’s as bad as I’ve seen it. The toxic environment has been building for a long, long time before Jan. 6, but Jan. 6 just blew it up in flames.”

Among Democrats, some have questioned whether they can or should even work with Republicans now. Democratic Rep. Jim McGovern said, “I serve with colleagues who I can’t even stand to be on the elevator with—their unapologetic embrace of the lies that led to violent extremism makes me sick.” Other Democrats fear that some of their colleagues may actually want to kill them, a sentiment that was likely exacerbated after some Republicans who had sympathized with the rioters quickly began ignoring the metal detectors that were erected outside the House chamber following the Capitol breach—and one actually attempted to enter the chamber while carrying a firearm.

Among Republicans, some have begun pushing a revisionist history of the events of Jan. 6, with one suggesting they were nothing more than a “normal tourist visit.” Additionally, save for two of its members, the House GOP made a show of not participating in the investigation into the insurrection.

Unfortunately, there’s no sign that these fraught relations will cool anytime soon. Several of the Republican candidates running for office in 2022 are Trump acolytes pushing the lie that he won the 2020 election, and many are likely to be elected in what should be a good year for the GOP. Rep. Madison Cawthorn is openly talking about an impending civil war while Rep. Marjorie Taylor-Greene has mused about a “national divorce” between red states and blue states.2 And Rep. Matt Gaetz previewed an even more combative post-2022 GOP majority:

(Update: this impending GOP antagonism now also includes possibly impeaching Biden—purely because Democrats impeached Trump.)

For their part, some Democrats have begun calling for the expulsion of colleagues who were implicated in helping plan the insurrection.3 Several have sought formal punishments against Republicans for other transgressions—and Republicans are indicating they will return the favor when they are next in the majority.

This all begs the obvious question: how does this period of ultrapersonal hostility end? I wish I knew the answer to that. In some ways, this has become a question of chicken vs. egg—will a focus on improving congressional relations and the institution’s democratic responsiveness restore voters’ faith in Congress and ameliorate their distrustful attitudes of government? Or does the change in Congress’s behavior ultimately hinge on how Americans, themselves, behave and what values they prioritize in their elected representatives? And, at a more basic level, how do you incentivize anyone to change their behavior in such a polarized time, when people see their political opponents as not just adversaries but threats?

Back in 2006, political scientists Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein identified Congress’s many shortcomings in a widely praised report. During the Obama presidency, they followed up with a book that offered several specific fixes for getting the institution back on track, including promoting reforms they believed could withstand the growing ideological gap and levels of contentiousness between two parties. (Unfortunately, the Trump era so exacerbated Washington’s problems that they were forced to update their outlook and acknowledge that change was even harder than they’d expected.) Some congressional observers have focused on things like expanding staff size to improve policymaking and increasing the work week to a full five days, which could give members (and their staffs) more time to cultivate the relationships of bygone years. Others have suggested changing how members of Congress are elected in the first place, including the creation of multimember districts and a shift toward ranked-choice voting, both of which could encourage candidates to appeal to voters beyond their own base and disincentivize extreme partisanship.

However, much of this may ultimately come down to Americans’ own behavior: can voters dial down their rhetoric, see each other less as enemies and threats, and prioritize bipartisan cooperation among their candidates for elected office—and, in doing so, produce a Congress that can work together to address the immense challenges facing the country? The future of our democracy may hinge on the answer to that question.

Gingrich famously led the charge to impeach a sitting president for the first time since 1868.